By Lucy

Trigger warning for medical details, child abuse, and also just being a really long post. Buckle up.

I was eleven when I found out I had cancer.

Except it wasn’t really cancer. Any doctor in the house will hasten to correct me that cancer is metastatic disease, and I’ve never had metastatic disease. Saying “I had a tumor” doesn’t have the same ring. Nowadays they have a new term for it, ‘previvor’.

As long as I had been alive, my father had had an ileostomy bag. He was shy about it, but my parents never tried to pretend it didn’t exist. We would joke about it, like blaming farts on him when he couldn’t fart. Occasionally it was a bogey-man; if you don’t eat your vegetables, you’ll end up with a bag like dad!

As far as I can piece together, through the haze of pre-adolescent memory and my parents just out-and-out not telling us things, my father started to get sick. That prompted the doctors to remind my parents that my brother and I could have the disease as well, as the disease my father has is genetic. So they sat me down and told me I had to get a colonoscopy.

Actually, just a sigmoidoscopy, but the result is the same. You have to fast for a couple of days, and take laxatives, and a doctor puts a camera up your butt.

The child abuse made everything worse. Ah, child abuse and cancer, two awful tastes that make everything infinitely worse. My mother had already stoked a fear in me, of cops and paramedics, that they might be pedophiles in disguise. I was absolutely terrified that I was going to be molested while sedated for the procedure. Far from reassuring me in any way, my mother told me that I had such a nice, cute, little butt that the doctors were going to love me. When I continued to resist the procedure, they threatened to beat me unconscious and bring me to the doctor that way.

Needless to say, I had the sigmoidoscopy. And it came back positive. There were polyps. I was tainted and cursed and diseased and disabled and worthless. Above all, worthless. No job would hire me, no man would want me, no insurance company would insure me.

By the time they decided to test my brother, they had sequenced my father. So my brother had a simple blood test that confirmed he was negative for the genetic mutation. Could I have had the same blood test? Did they just feel like torturing me? Questions I won’t have answers to.

What I have is called Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. You can google it, but you won’t find more than I’ll tell you here. It’s a rare disease. The internet says there’s an incidence of 1 in 10’000, but that means that with roughly 150’000 people in Barrie, there should be fifteen cases and I’ve only met one other person in Barrie with it.

There is one certain path for FAP; it causes colon cancer. Before 30, usually. They monitor you with colonoscopies until the polyps reach a point where it seems like one might metastasize, then they remove your colon. Technically they could just remove it right away when you get diagnosed, because it will never not cause cancer, but there’s a quality of life aspect.

After that, it’s anyone’s guess. It causes a myriad of things. Cancer higher up in the GI tract is guaranteed, but where in the GI tract the cancer reoccurs varies from mutation to mutation. Duodenum, stomach, esophagus. It causes freckles in your eyes; if your optometrist ever tells you you have freckles in your eyes, get a colonoscopy. It causes odontomas, non-malignant bone cancer in the jaw. The real thing every FAP patient is terrified of is a Desmoid. It’s the grim reaper on your shoulder.

I’ve been lucky – I’ve met people with such active disease they had their colon removed before 14. But mine was indolent for a long time, I had colonoscopies every two years. It would be a lot for any child to process, and I had my parents filling my head with nonsense and abusing me, so I just didn’t process it. I didn’t need to. It was a distant thing, not currently affecting me.

The same was not to be said for my father, who was fading before our eyes. When I was a child, my father was a giant. He was 200 lbs of solid muscle. He ate a lot, healthy food, and he worked out every day. To this day, I still refer to taking a large bite out of something as a daddy bite. There was nothing he couldn’t lift, and he never slowed down. When the factory forced him to take vacation time before it expired, he went out to the store, bought paint, and painted all the trim in the house in a single day because he couldn’t just sit still. He rented a scaffold and redid the siding on the house. He had two cars (in addition to my mother’s) and did all the maintenance on them, and washed and waxed them weekly.

We found out later, the cancer had come back in his duodenum and pancreas. It caused him pain every time he ate. Then it caused him pain when he laid down, so he spent every night on a reclining chair in the living room. He was on Hydromorphone, then Percocets, then Fentanyl before the opioid crisis made that a household name. He lost weight, and lost his temper. His hair turned grey and fell out, and his eyes looked like billiard balls glued into a skull. He was the ghoul in the living room we tiptoed around. It was hard for a teenager – I was as scared for my dad as I was scared of my dad.

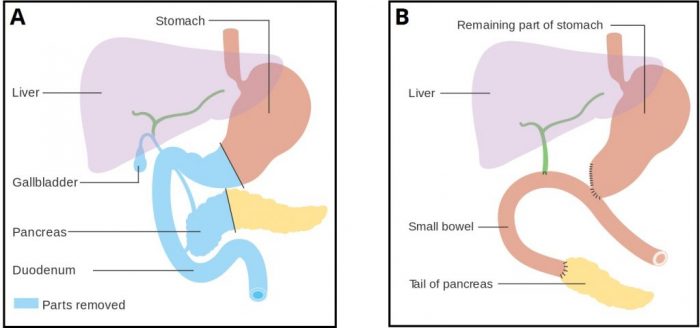

When I was sixteen, they finally had a surgery for him. It’s called the Whipple. It’s one of those surgeries where you’re almost better off just dying. They remove your duodenum, your gallbladder, part of your stomach, part of your pancreas, and then stitch what’s left back together. Without a gallbladder, you can’t process fat, so bacon is out. With a severely maimed pancreas, you’re pre-diabetic at best, if your pancreas doesn’t just give up and you become diabetic immediately. And with no colon, your very short intestines develop Short Bowel Syndrome, where you just don’t have enough guts to absorb your food properly. The surgery takes 12 hours and you have a 60% chance of just dying right there on the table. Half of those who survive it die within a month of the surgery; my biological grandmother was one of those people. We were prepared for my father to die; my grandmother and my aunt flew up from Nova Scotia to see him, to be there in case there was a funeral.

Miraculously, he survived. Probably in no small part to how healthy he had tried to be all his life. But he never really came back to being himself.

My father has told me, at the time the doctors told him he would be dead within five years, but if he could go back in time he’d decline the surgery, knowing he would be dead by now. Which is why I always tell people I won’t see 60; my grandmother had the surgery before 60, and so did my father. And I won’t do it.

Colon Removal

I was nineteen when they decided to remove my colon. My surgeon offered radical colonoscopies, where they try to remove as many polyps as they can, every six months to delay the surgery. I declined. It had to happen sooner or later. At the time I was in college, and I thought I’d rather get it done when the most stressful thing in my life was making sure I caught the train on time. I had the surgery set for when exams would take place. I got a note from my surgeon, and I went around to all my teachers and told them I’d be out of class two weeks early, and I wanted all my assignments and exams now. And I did it. I finished, and passed all my courses, two weeks early, planning for a life-changing surgery.

The child abuse was the worst part. My mother insisted I live at home while I was in school. She paid for my transportation and food, but she didn’t make it easy. I was in school for Fashion Techniques and Design, at George Brown. Fashion is not a course you can just buckle down and study. You need to be at school, using the specialized tools there that you can’t bring home. You need to go to industry events. You need to be in the city. But she insisted I was some sort of alcoholic party animal. She went out of her way to make sure I had to come home and cook for myself. She threatened to kick me out if I didn’t get the first train home after classes were over, instead of staying at school to work on my homework, and she kept my schedule on the fridge to hold me to it.

When I told her about the surgery, she told me my boyfriend at the time would not be allowed to visit me, during the three weeks I would be bed-bound.

Are there worse things than not having your boyfriend visit? Sure. But it was the intention of cruelty. She wanted to keep me isolated, to force me to recover from the surgery on her terms, not on the schedule the doctors or my body set for me. I told her I was moving out, and she told me I wasn’t allowed to.

I left in the middle of the day. My boyfriend was 8 years older than me, and he had a car and an apartment. I’m still not sure if it was the brightest idea, but it was made from desperation. I packed up everything I needed for school and we threw it in the car as my mother stood in the front door, baffled. That was a month before my surgery.

I spent the month before I lost my colon adjusting to having fled from my childhood home. Finishing my college courses.

I wasn’t nervous about the surgery. I just didn’t process it. It was inevitable, so I didn’t think about it. The surgery took 6 hours. It had to be in two parts. The first part was to remove my colon and create what they call an internal pouch, a J-pouch. I’d have a temporary ileostomy while my insides healed. Then, in three months, there would be a second surgery to close the ileostomy and hook up the J-pouch.

I told my mother when it was, for some reason, and she showed up over my protests. I remember, when I woke up the nurse asked who I wanted to see, and I said my boyfriend. The nurse came back a few minutes later and said my mother was insisting on seeing me first. I told the nurse I didn’t want to see my mother at all.

I remember why. It was money. I was a broke college kid, a new cancer patient. She offered me money to keep talking to her.

I was in the hospital for a week. The first day I had a catheter and I couldn’t sit up. They gave me a pain pump and I abused it. I was terrified that if I waited too long, I’d be in excruciating pain like dad. Every time I pressed the button, the medication was so strong it knocked me out. I slept a lot the first couple of days. Eventually they weaned me off, although they kept both IV’s in, not connected to anything. They got coated in bloody scabs. I started eating jello and pudding, before moving on to real food. I got better fast, but then I wasn’t really sick to begin with.

At one point, the girl in the bed next to mine was also an FAP patient. She was younger than me – they had removed her colon at 14, but it wasn’t enough. I forget the details of why, but she was in there for an experimental procedure. They had cut her open and put the chemo directly in her guts, and sewed her back up again. There were constantly people at her bedside. She never slept at night and she threw up all the time. My mother exchanged numbers with her mother, but we never heard from her after I left the hospital. We think she died and she wasn’t even 18. I am one of the lucky ones.

People came to see me in the hospital. People from Barrie, people from school. I was baffled. That’s how child abuse breaks you. I had no concept that people would want to drive an hour and a half to downtown Toronto to talk to me while I laid in a hospital bed. My experience was that my sickbed was a penitent cell, from which I might meditate on how I had inconvenienced my mother by becoming ill. The surgery was good for me in that sense; it taught me that people care. If anything, I loved being fussed over in the hospital. It seemed like a vacation. The hospital food was great because I didn’t have to cook it or wash the dishes. I didn’t have to vacuum the floor or change the sheets. People brought me gifts.

Going home was the hard part. My boyfriend had been renting a room when I moved in, so we upgraded to a one bedroom apartment. It was a decent size, only 900 a month. Nowadays 900 will get you a room. I applied for welfare and got it, only 850 a month, but he was working full time, so our bills were manageable. Ostomy supplies at the time were 500 a month. There were grants to cover part of the costs, but they wouldn’t give it to me because I had a temporary ileostomy. It cost me extra, my ostomy kept trying to pull back inside my skin. An ileostomy is literally just a loop of your intestine hanging outside of your body. It looks like a red, bloody lump. You have to fit the bag to the ostomy, because bile is basic, or alkaline, which means it dissolves your skin. If your skin starts bleeding and peeling, then the ostomy bag doesn’t want to stick to it, which just escalates from there. So I had to spend extra for bags that fit extra close, and these little plasticine rings to go around the ostomy and protect my skin.

My boyfriend was good at the time. He would help me change my bag. He’d always ask the nurses to be there when he was home, and he’d sit and talk with them about how to take care of me, and they told me most guys his age would have left by now. So we got engaged. It just made sense. If everyone else would have left, he was a keeper, right?

My second surgery was delayed. The surgeon is very, very good, which means he’s in high demand. I kept getting bumped for people with more urgent concerns than closing an ileostomy. The start time for my second year of college came and went without me and I never went back to school, another thing cancer has taken from me. It took me so long to get back to work and start saving for school again, and then I got sick again before I could. At this point I’ve given up going back.

I had my second surgery two days before my 20th birthday. The doctor offered to delay it so I wasn’t at the hospital for my birthday, but I just wanted it done with.

I was only in the hospital 3 days this time. They just wanted to make sure everything had hooked up properly. Lots of people have problematic closure surgeries and are in and out of the hospital, but mine was a breeze and I felt back to normal. Within a month I was looking for work.

That’s where disability sucks. Employers just saw the gap in my resume and assumed I was some lazy kid. I never got interviews to explain that I had had surgery, but it might not have helped. They might even have just looked at me having had surgery so young and decided that I was a risky investment. Someone I knew at the time recommended a temp agency to me, so I went in. I was halfway through filling out the paperwork when someone stuck their head in. “You do sewing, right? Industrial machines?” I was hired. There is lots of industrial sewing machine work in Barrie. I went from being unhireable to having companies trying to bid over each other for me.

Vincent

I found a good place to work and settled in. We started planning the wedding. I wanted kids – I’d wanted kids for a long time, although I knew it was going to be an uphill battle because FAP was genetic. The cheapest option, in Ontario anyway, is to get pregnant and then get tested. After six months of trying, I got pregnant. I was pregnant at the wedding. They can’t do the test until you are in the second trimester, so I had Schrodinger’s pregnancy. It was a bouncing baby boy by the time they could test him. I still remember his ten little toes on the ultrasound. I named him Vincent.

When I don’t want to tell the whole story, I just say that I lost him at 16 weeks.

He was fifteen weeks and five days along when they told me he was positive. They offered me a few days to think about it, and to talk to a therapist. It didn’t feel like a choice. I just kept seeing my father’s face, gaunt and skeletal, his hair grey and falling out. I was going to be in that hospital bed one day, telling my son I had cursed him. I couldn’t do it.

It’s not a small thing. Babies are viable at 20 weeks. He was 4 weeks away from being able to live outside me. He was so, so close to being in my arms, my little baby boy!

I stopped talking to my mother after I lost Vincent. She tried everything in the book to convince me to keep him. My parents had led me to believe they didn’t know that me and my brother could get FAP from my dad. When I pointed out to her that I had that knowledge and couldn’t ignore it, she finally confessed that they had known and decided not to test us. They had hoped we’d be living in the Jetsons by now, when they could clone organs and easily cure tumors. It was a mistake on her part. The fact that she had known was the final straw. I haven’t talked to her since.

I couldn’t do it again. I decided that the next time I got pregnant, I’d do IVF. I’d get the embryos tested before implantation. I couldn’t lose another baby.

It broke my husband too, I think. I don’t think he ever really processed it, despite caring for me after the surgery. He started cheating on me. He started smoking again. He kept getting fired from jobs for being late or being inappropriate. I was 21, and less than a year after the wedding I had one foot out the door. I was torn, because I felt like it was my fault for being sick, but staying wasn’t really doing anything but making both of us miserable.

Desmoid Tumor

My condition escalated.

It wasn’t supposed to. Both my father and my biological grandmother had been fine after their initial surgeries. The cancer had come back in their duodenum in their late fifties. I was 21, I was supposed to be fine for thirty years. But I wasn’t.

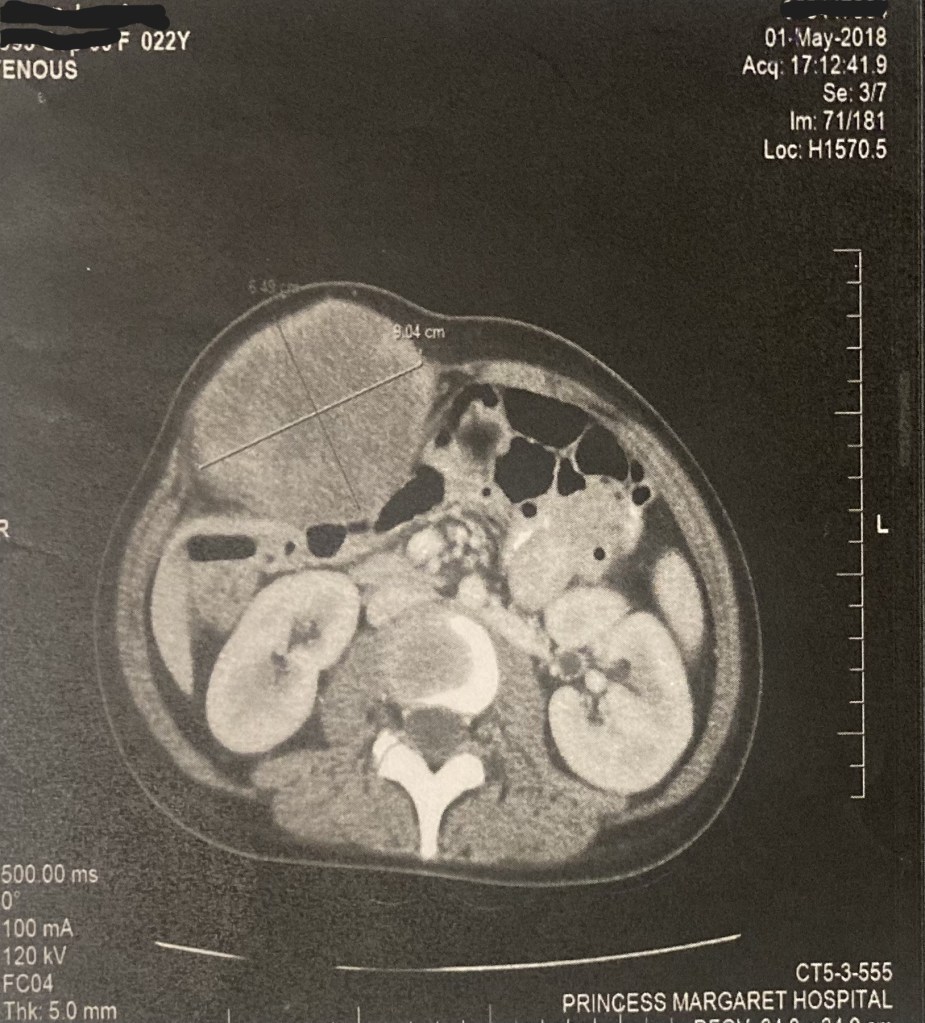

It started as a lump. It looked like a golf ball, placed just under my skin, next to my ostomy scar. I had an appointment planned for November to see my surgeon, so I just mentioned it to him then. I thought it was a hernia, weakened abdominal muscles, or scar tissue. But then he said those fatal words.

“I think it’s a Desmoid.”

The scan was sort of absurdly funny. He booked me a scan at RVH, because he could just call and tell me yay or nay, no need to drive down to Toronto for a MRI. But the technologist, who didn’t know what the tumor is because few people do, just told my surgeon there was nothing on the scan, and he had to call and yell at them to send him the images so he could see. It took them a month to send him the images, literally on a DVD in the mail instead of an email for some nonsensical reason.

It was a Desmoid.

It was the worst news. It was the death knell for so many people with FAP.

Normal people can get Desmoids. They are, simply, a sarcoma, a soft tissue tumor. In normal people, they have no metastatic potential, are slow-growing, and respond well to surgery. In people with FAP, they kill you. They grow at an insane rate, and they come back after surgery. Worse. They come back faster and bigger every time you try to cut them out. Surgery is the gold standard for Desmoids except in people with FAP. They just kill us faster.

It’s a cancer of scar tissue, the scar tissue my guts were now wrapped in from my colectomy. There could be tumors all over my insides at any time and I became a ticking time bomb. Any future surgery can become another Desmoid. I could get in a car crash and need surgery to treat internal bleeding or a broken bone, and that could become a new Desmoid. I was 21 and a dead man walking.

He referred to me a Desmoid specialist right away, and it took less than a month to see her. But in the two months since I had first noticed the golf ball, it had doubled in size to a baseball or grapefruit. I stopped wearing the form fitting clothes I loved and hid inside baggy sweaters. I was a health nut like my dad and proud of my six-pack abs, even after the two surgeries, but it was too embarrassing. She told me that she couldn’t operate on it. She referred me again to a sarcoma specialist who could order chemo.

The specialist told me most Desmoids are indolent and that she wanted to watch it. I told her it had doubled in size within two months. She doubted me and ordered another MRI and a biopsy. When it came back, it confirmed I was right.

There was a flurry of activity. Within a month I’d had another surgery to install a Port-A-Cath. They put me on Methotrexate and Vinorelbine. Methotrexate is pretty tame as far as chemo goes – they give it to people for arthritis. It’s well tolerated and causes few side effects. Vinorelbine is acid in your veins. It has a high rate of venous extravasation, meaning it leaks out of smaller veins and destroys the tissue around it, so they needed to make sure it went into the biggest vein possible, the jugular. The port sits under the skin on your chest, and the line hooks over your collar bone and goes into the jugular down to your heart.

I actually loved the port. I explain it to people as being like a socket. Instead of hunting for my famously small veins, the nurse can just plug in an IV to it. I could have MRI’s with it, get blood drawn, anything at all. I miss it now. You have to have it removed if it isn’t being used or it clots up.

The chemo schedule was once a week, for three weeks, then one week off. It would be over the course of two years. It was revolutionary, the idea being that it was such a low dose I could work full time and be fine. And I was fine, for a bit. They give you steroids with chemo. I figured out pretty quickly that the steroids actually made me feel fantastic for the day after my treatment, then I crashed the day after that. I had my chemo on Thursday before work (I was on afternoon shift) so I was fine Friday, and then Saturday was when the crash hit, so I didn’t need to take time off work.

I was the first to get this treatment at RVH. The doctors were actually nervous about letting me do it there, but I insisted. The first thing the doctor at RVH said to me was “I know you know more about your condition than I ever will, so I will defer to you on everything”. Within a year, they had treated three more people at RVH with my treatment, with knowledge from treating me. People who couldn’t drive to Toronto. Those are lives I helped.

The tumor kept getting bigger for six months. People started asking me if I was pregnant, that’s how big it was. I went back to my maternity clothes. I felt damned- I had traded in my son for this demonic cancer baby thing. I also felt more sure that I had made the right choice to give him up. I would be going through chemo while trying to raise a toddler. Despite my parents thinking I’d have an easier time, I had a worse time. Who knows what life would have been like for Vincent?

I lost weight. It was a one-two-three punch.

- I was sick from the chemo, as everyone knows chemo makes you nauseous.

- Tumors need to be fed. They are fascinating, they produce hormones to create their own arteries and veins to get blood flow to every part of themselves. It consumed my calories and my nutrients.

- And it was growing into my intestines. Every inch it gained was space my guts needed. I was already restricted in what I could eat, and the pool kept shrinking. It was a desperate race to find out what I could eat, how we could force calories into my body. Eventually all I could have was blended soup and Ensure.

At my worst, I was 90 pounds. I was badly anemic – I’ve always been on the edge of anemia, but with the tumor consuming my blood, the chemo impairing my ability to recover, and my general malnourishment, bad turned into worse. They had me on blood transfusions every two weeks to try and keep me alive long enough for the chemo to save me.

Eventually it got so bad I couldn’t eat at all. Even drinking water made me throw up. That’s how the tumor was going to kill me, by starving me to death. At one point they even put me in palliative care and discussed end of life plans with me. I was put on an IV for the weekend and told not to eat or drink, to give my guts a chance to rest. If I couldn’t eat again, that was the end of the line for me.

I was depressed. How could I leave my husband and move out on my own when I was dying of cancer? I was on hydromorphone for the pain. I was too ashamed to have friends over because my husband was fully abusive by that point. I didn’t post on Facebook for two years. I stopped leaving the house except to work and go to the doctor. Finally I stopped working and waited for the tumor to kill me. I prayed for death.

Then they told me; it’s shrinking.

I was getting better. I was going to be ok.

People tell you you have to be positive when you have cancer, but they’re putting the cart before the horse. In hindsight, a lot of my symptoms were the fact that I had given up and stopped fighting. If I could go back knowing what I know now, I would have left my husband before I started treatment, so I’d be in a more positive environment to heal. Once I was in it, it was hard to be like “ok, I’m doing chemo, and I’m working full time, and I’m trying to leave my abusive husband when I’ve never lived by myself and have no family to stay with”. But I didn’t know. Who would, at 21?

I was on disability, but it wasn’t enough. Between trying to care for me and the mental health problems my husband had, he couldn’t work enough to keep the bills paid. We slipped into debt. Hospitals are expensive – parking at RVH was 20 dollars for each day of treatment. 100 dollars a month was another expense we couldn’t handle. Rent for a one bedroom was 1’100 at a time when disability paid less than that. There was food, internet, the car insurance. We were drowning.

I debated stopping my chemo to let the tumor kill me. I tried more than once to kill myself. I succeeded, once, but my husband revived me. One time, in an ambulance to the hospital for something cancer related, the paramedic told me how much he hates having to transport suicide victims, and that was enough to scare me into never mentioning my depression to my doctors.

When did I get better? Yahtzee inspired me. I’ve been a fan of Zero Punctuation since I was sixteen. When I was 23, towards the end of chemo, his company got bought by a Canadian company and they brought him to Toronto for a show. I asked Oma for the money to go. I was too nervous to talk to him. My husband asked him for a picture with me. He tried to put his arm around me for a picture and I shrieked and ran away.

I got better. Sometimes action comes before motivation. I finished chemo and went back to work. I got paid a lot – they gave me a dollar raise every year. I started to cover the bills and pay down the debt and I realized I was over the hump. The tumor was still there, but it had shrunk to the point it wasn’t a problem anymore. I have scans once a year to confirm it isn’t doing anything exciting.

A coworker, who heard I was planning to leave my husband, offered to let me rent a room from him. After some time, I took his offer. It wasn’t what I planned for my life, but it was an option to leave my husband.

Survivorship

Recovering from cancer is almost more difficult than enduring it. Everyone has these expectations that things will just magically go back to normal.

They did not.

When I was bedridden and starving to death, I had lost all my muscle. I almost had to relearn to walk. Before cancer, I was ripped – I had a six pack, and I was starting to work on the V muscle. When I had started recovering, I put weight back on – and not the good kind.

By the time I was finished chemo, I had gained 20 pounds more than I was before chemo, but it was fat. No matter, I’ll just hit the gym and be ripped again in no time.

It didn’t happen. I was inexplicably tired, or inexplicably to me. I struggled to find some level of exercise I could manage. Even walking around the block left me winded, and continued to do so for months.

Me and my husband were separated for six months when I started dating again. I still desperately wanted kids. Now I was 24 and I could hear my biological clock. The doctors confirmed that chemo had depleted my ovaries. IVF had to be sooner rather than later.

Then the pandemic happened. I moved in with my then-boyfriend and his family, maybe too early. I was just putting my life back together after chemo and the pandemic shut everything down. I had a hunger for life. I wanted to buy a house. I wanted to get married again and have kids ASAP. I made some silly choices trying to catch up on the four years I’d lost.

I pushed myself constantly. My partner’s step-dad owned ten acres outside town. He had recently broken his leg and was not very mobile. I was more than happy to be given the most physically demanding tasks. I swam laps in the pool when the weather was good, and I ran laps of the yard when it wasn’t.

My then-partner had a lot of problems, but one good thing about him was that he was always a dreamer. He unlocked the ambitious part of me. My job was safe and well paid, but there was no upwards mobility.

I got a new job. It was a pay cut, but there was the allure of bigger and better things to come – after 6 months probation, I could apply to move upwards. They employed millwrights full time, and that’s what I wanted.

The job wasn’t even as physically demanding as my old job. But it was 12 hours, much of it standing. We couldn’t turn the machines off to go to the bathroom, we had to be tapped out. If things were hectic, we were short-staffed, or someone just had a grudge against you, you could be there trying not to pee yourself for a while. Breaks were whenever time could be spared for the supervisor to run your machine for fifteen minutes.

I scoffed – what is standing for 12 hours? Easy, right?

But I couldn’t manage it. No matter how hard I pushed myself, I simply wasn’t putting on muscle. I was exhausted and in pain. The job never got easier. The physically demanding chores around the house were now mine, whether I wanted them or not. The six month probation period came and went, but I never moved up within the company, I suspect in part because of my health problems. Which is honestly the stupid part of the career ladder, because I would have been more productive if they had taken me off the hamster wheel and promoted me, instead of insisting I proved I could run on it.

It couldn’t keep going. I started collapsing at work. I was passing blood, and throwing up blood. I couldn’t keep food down. Eventually someone called an ambulance (after several weeks) and made me go to the hospital.

The doctors scanned me.

Intestinal obstruction. You need surgery, now.

I refused. Surgery was synonymous with death to me now. Surgery meant another Desmoid, and I had barely survived the first one. I insisted to be transferred to Mt Sinai so my surgeon could take care of me. The surgeon at RVH was gracious enough to allow me to check out, and called ahead to Mt Sinai so I could be admitted quickly.

I spent five days as an inpatient in Mt Sinai. My surgeon was on vacation, so no one knew what to do with me. Bowel rest and observation. And painkillers.

I am eternally grateful to him for making me a priority. He ran back in to the hospital once he got back from vacation, still in his civvies and not officially back on duty. He wanted to scope me, top to bottom, but he was fully booked for the next week.

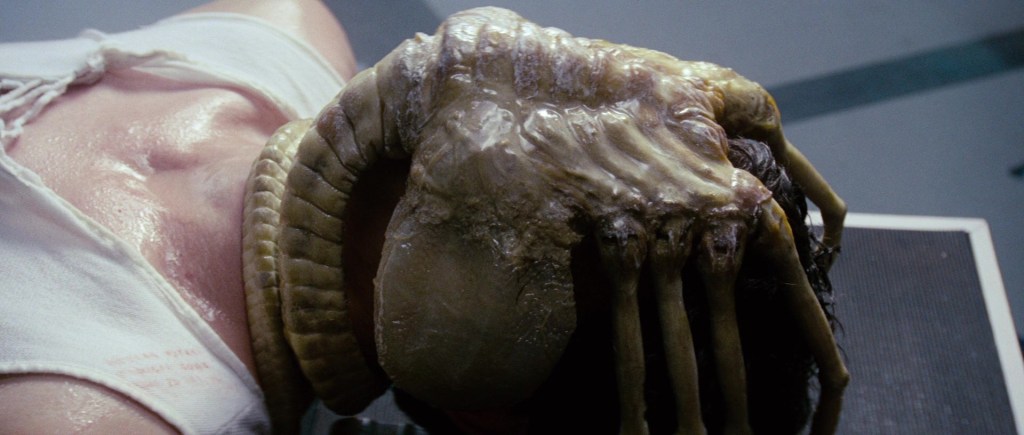

I could be squeezed in for a scope between patients the next day… if I wasn’t sedated.

I was not looking forward to that idea. However, my other option was to languish in the hospital, slowly dying, until someone had a free spot for me. So I had a colonoscopy and an upper endoscopy, very, very mildly sedated. They gave me something to numb my throat, but nothing really prepares you for being fully aware of the long thick snakey camera being shoved down your throat as every part of you rebels and you vomit up stomach acid. It was very much like being impregnated by a facehugger.

Adhesions, was the final decision.

Nothing they could do.

Adhesions are internal scar tissue. Usually, they are left alone unless they are giving you hell like I was currently experiencing. However, the only real treatment is more surgery to remove them and hope they come back better – which wasn’t a real option with the looming threat of desmoids.

Eat what you can, my surgeon advised me.

Still, there was no reason for why I couldn’t put on muscle. I went to my GP multiple times for help. She tried to fob me off as depressed and put me on anti-depressants, but the depression was an effect, not a cause. Finally she referred me to the cancer survivorship program.

*Record scratch*

Did it occur to none of you PhD’s that the cancer patient should go to the cancer survivorship program?

They gave me the works, just as well cuz I deserved and earned it. The nutritional program was unnecessary – at this point, I could probably write the book for it -but I went to it anyway, just to be co-operative. They ran endocrine tests and a stress test on my heart, all of them good.

The most helpful thing was the simplest. They sent me to a physiotherapist, who prescribed me some simple strength-building exercises and stretches, and loaned me a Fitbit. For most people, a Fitbit is useless, if you lack the motivation it won’t suddenly gift it to you. But I was 1000% motivated, and the Fitbit was a wealth of knowledge into how my broken body was functioning. When I had to give it back to her, I bought my own and I wear it religiously.

For the first time in 4 years, I started putting on muscle. I started feeling good again.

Having a kid, Round 2: IVF

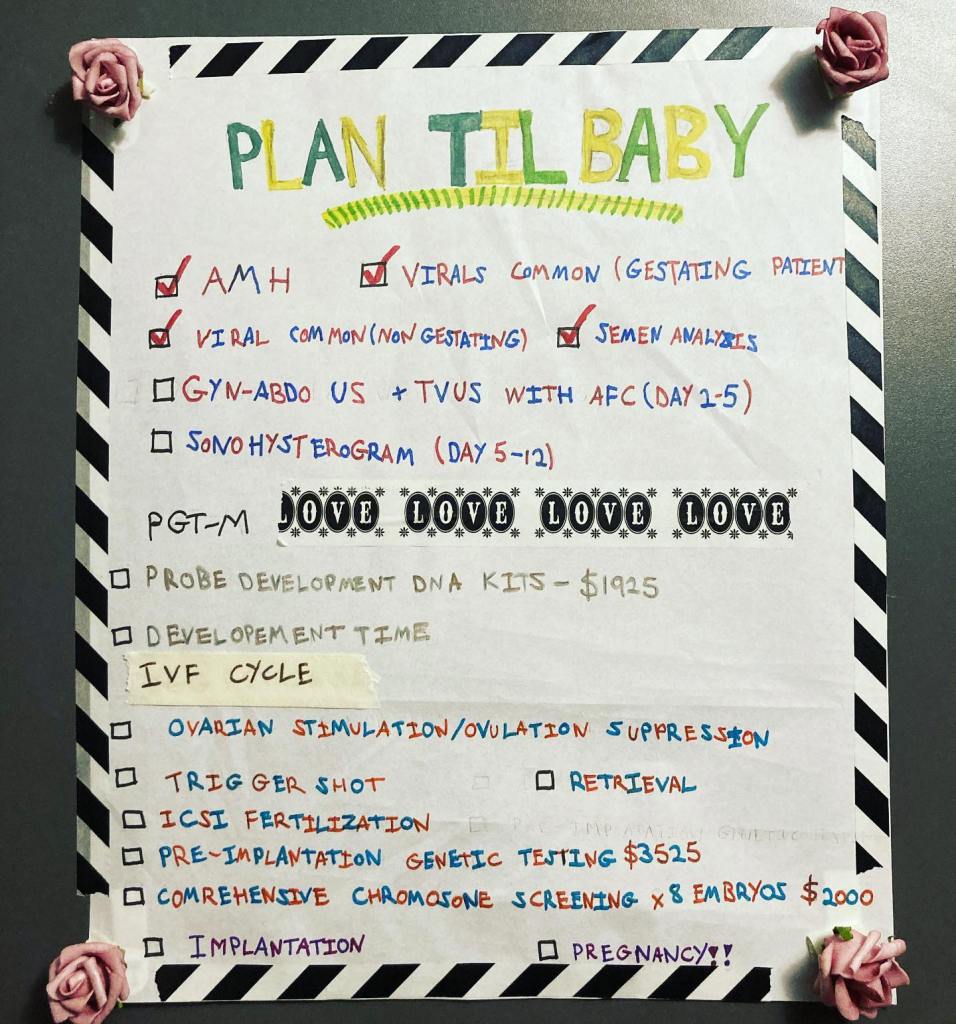

We tried IVF. IVF is hard and expensive, but in Ontario they cover one cycle of it. With work covering my drugs, the real problem was the extra expense of getting the embryos tested. It costs eight grand on top of everything else and takes three months to set up.

They sequence you and your parents and your partner, and they make what they call a probe. They do this before they remove the eggs. Then they’ll test all the eggs using the probe and you have the option to discard any that come up positive. It’s a rotten numbers game. They predicted they’d extract 8 eggs, and 4 would be non-viable for whatever reason, and 1 or 2 might be negative for FAP and viable. Or all 8, or none. I might spend eight thousand dollars to have no viable eggs. There’s no way to know until you do it.

I got the probe done. Then the government funding got all fucked up. They ran out before the end of the year, so I had to wait for the next calendar year to start the extraction process. But in December, we were served an eviction notice. My landlord wanted to sell the building while the market was hot, and he’d get more money if it was empty. He offered us 3 grand to walk away, and we couldn’t afford to not take it. But we couldn’t find an apartment that made sense; 1 bedrooms in Barrie were 1’300 at that point, and we wanted another room for the very expensive baby we wanted to have.

In 2022 I finally realized it wasn’t working. I broke up with my boyfriend and moved back in to the room I was renting before.

I started the carpenter apprenticeship because it was offered to me. I struggle with men’s expectations, that I am slender because I am a girl. Should I correct their assumptions – it’s actually because I am a cancer survivor? Or just let it go?

I puttered along for a year, sort of frozen and undecided on what I wanted, where I should be.

The Next Step

Moving to Thunder Bay meant giving up things. It meant I probably wasn’t going to go back to college and finish my certificate. It meant that I was unlikely to be able to access IVF, especially the specific genetic sequencing I required.

I didn’t really change anything, but after I met the Vagabond, I changed. The chemo weight started coming off, and my muscle growth improved. The adhesions magically went away, and I was able to resume taking Metamucil and eating vegetables again. Was it the glow and optimism of love? The air around Thunder Bay? Some strange coincidence – months of steady progressive suddenly kicking in all at once?

In May 2024, I was finally able to push my heartrate above 150 during exercise, the last real hurdle.

2023 was the best I’ve felt in 7 long years, since I started chemo. Being up here, travelling without a care in the world.

I still want it, the house and the kids. But I’ve let it go. I’ve learned how to want something while knowing it isn’t practical to have it.

That’s where I am now. I still have the desmoid, but I’ve been off treatment for five years now. Vincent would be seven if he had been negative.

Now I just wait for the ax to fall again.